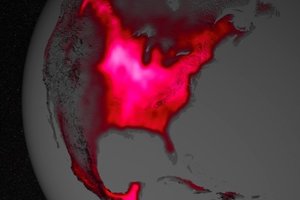

According to a recent NASA news release, data collected via satellite sensors shows that during the Northern Hemisphere’s crop growing season, the Midwest region of the United States vaunts more photosynthetic activity than any other spot on Earth.

In addition to converting light to energy via photosynthesis, chlorophyll in healthy plants also releases absorbed light as a fluorescent glow that is invisible to the naked eye. The amount of glow given off by plants is a prime indicator of the amount of photosynthesis, or productivity, of plants in a given region, making measurement of the glow a valuable asset in estimating large-scale growing success.

This research, which was led by Luis Guanter of the Freie Universität Berlin, who used fluorescent plant data for the first time to estimate photosynthesis from agriculture, was published in the “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,” March 25.

Co-author of the publication, Christian Frankenberg of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., said in the release, "The paper shows that fluorescence is a much better proxy for agricultural productivity than anything we've had before. This can go a long way regarding monitoring – and maybe even predicting – regional crop yields."

NASA says data showed that fluorescence from the Corn Belt, which extends from Ohio to Nebraska and Kansas, peaks in July at levels 40% greater than those observed in the Amazon. To validate the measurement of fluorescence for crop yield purposes, researchers compared the data with ground-based measurements from carbon flux towers and yield statistics which confirmed their findings.

The accuracy of these findings could present crop producers with new agricultural data to help plan and predict areas of successful yields in the future.

Image Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center